C^3: Current Commentary by the Council

Are you listening? Have you heard the voices of your students? This time of transformation might be your best opportunity to do so.

Our students’ guts are screaming that something is wrong. The academic programs offered to them during the coronavirus pandemic have increasingly avoided addressing their very real human needs in favour of evidence-based learning—a term that distorts the complex existence of human beings alongside one another. Unfortunately, we’ve been largely unable to voice our baser instincts, those feelings that come before consciousness and unconsciousness (D’Amour 2019). What could be used as evidence to inform teaching practices has largely been unspoken, unvoiced, unheard and, in some cases, ignored in favour of the evidence that officials and researchers alike have decided is important enough to become the basis for our evidence-based programs.

Even students who excel in school have been left speechless, unable to find their voice in this new environment, unable to identify their own learning needs or communicate with those of us who care for them. This, I think, has only become more pronounced during this pandemic, as we’ve raced toward at-home learning delivered to solitary students with preconstructed programming and materials that hold little or no opportunity for the human. For what room is there for the human in a program designed for the demonstration rather than the learning of a skill?

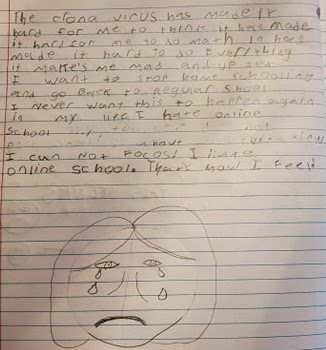

But a special few, such as this young lady, the daughter of a friend of mine, have broken the silence and expressed what I have been unable to express from my vantage point:

The corona virus has made it

hard for me to think it has made

it hard for me to do math it has

made it hard for me to do everything

it makes me mad and upset

I want to stop homeschooling

and go back to regular school

I never want this to happen again

in my life I hate online

school

I can Not Focus! I hate

online school. That’s how I feel!

In reading this poem, I am reminded that it is the lived experiences of my students that should inform my practice. Is it ethical, then, to advocate for online learning if the experience effectively brings a student’s love for learning to an end? Is my admiration of online learning opportunities justified? Are the meaningful experiences that I intended materializing? Have I even begun to address the primal, undetectable, unmeasurable, unwritten somethings that have scraped their way upward and outward during this time of unease through the voices of children? Or have I been so blinded by the utility offered by technology that I’ve failed to notice the loathsome human experience it offers or, worse, intentionally ignored it? Is it time to re-examine students’ experiences in light of these emerging voices? Have I asked myself how I might begin to listen for other voices? How might this evidence that I’d unintentionally ignored inform my classroom practice? Might it also have an impact on the use of standardized assessment, meritocratic structure and the privileging of measurable data in my classroom? And if after asking all these questions and more, I determine that something needs to break, I imagine that it shouldn’t be our students.

References

D’Amour, L. 2019. Relational Psychoanalysis at the Heart of Teaching and Learning: How and Why It Matters. New York: Routledge.

Darcy House